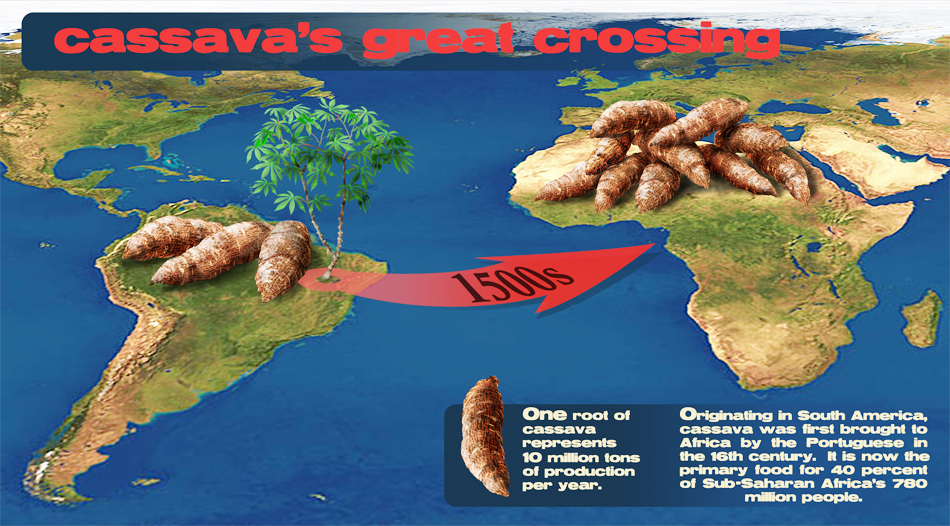

Cassava is a profoundly vital plant that can take credit for sustaining millions of people (i.e. poor farmers and their families) every day across the tropics, especially in Africa. Africa produces more than the rest of the world combined for many reasons: it grows well in poor soils, is drought resistant, and can be left in the ground to be harvested when convenient. I am fascinated by the human and natural history of all cultivated plants (and thus foods), so I created this graphic to explain the journey this plant has taken from South America to the main staple of Africa.

My own first experience eating cassava dates back to when I visited Madagascar. In the arid central south, it was sold ready to eat much like a baked potato. I thought it was flavorless but tolerable, and I ended up eating a lot of it because it was the most accessible food and easy to carry on my bike.

Some years later when visiting Cameroon, I again ate a lot of cassava, but this time pureed, boiled, then cooled in a long rubbery baton du manioc called “Mbobolo”. It felt like a giant prosthetic ET finger! You would unravel the cassava tube (~2 feet long and ~1 inch in diameter) from its tight banana leaf wrap, and dip the semi-opaque rod into a folded-banana-leaf satchel of spicy peanut butter. Scrumptious.

And it was there in Cameroon that I learned that cassava had to be processed to be edible- well, I mean eaten without giving you goiter, paralysis, or disease! There are malevolent forces (science calls it cyanide) ready to wreak havok when one eats cassava not thoroughly processed. There are a few ways different culinary traditions do it, but generally it is to let it soak in water and ferment for hours or days.

Here are 2 resources…this one on how and why to incorporate it into your baking:

and of course wikipedia’s article on it http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cassava

Yeah…cassava root. It’s like a potato but with a horrible consistency, that milky, chalky liquid when you boil it and that unforgettable flavor of nothing. YUM! Try it with a boiled green banana for added blandness. Oh, and if you hate crapping, this is the food for you! The “C” in cassava is for constipation.

Sweet graphic though!!!